Written by Ashton Brown, (Howard University), Student Correspondent for CET Brazil, (Business at FGV track), Spring 2025

It’s Monday at 12:50pm. I just got out of Portuguese class at the CET Center in Perdizes. I likely rushed out of the crib that morning, skipping breakfast. I need to eat something before I take my 30-minute bus ride to Bela Vista so I can make my International Monetary Finance at FGV class by 3pm so if I’m going to eat out, I should probably get something nearby.

I’m hesitant because, as we were made aware in our first few days here, we live in a particular neighborhood. Perdizes is a more affluent, elderly, trendy neighborhood—which automatically signals to me more expensive plates that are smaller in size and likely not as flavorful. The kind of places that serve food that looks great on Instagram, probably healthier meals, but not going to fuel me for the rest of my day. CET is very adamant to remind us that this area is not representative of all of Brazil, or even São Paulo.

I sat down at Estrelas, a restaurant across the street from my local bus stop. I ordered (with some slight difficulty because of my “sotaque gringo”—Portuguese for sounding as American as LeBron James) a prato feito. It’s a classic Brazilian dish that includes rice, feijão (black beans), a choice of meat–mine a well seasoned grilled chicken breast–fries and a salad. I also get a refreshing Guaraná soda to wash it down, Brazilian style. This is about 1200 calories of straight fuel. It’s heavy, but it’s typical in Brazilian cuisine and I’m starving up until the plate is set in front of me.

I grit my teeth as I go to check out…the cost of a meal the size of two meals will certainly be a blow. As I checked out, the attendant’s quote was met with my surprised face.

“Vai ser R$42.50,” she says with a smile. “Credito o debito?”

I had this look of astonishment on my face not because the number was so high—a $42 lunch in the United States would have required me to wash dishes to make up the tab. The shock came as I estimated the conversion to USD. As I write this, the exchange rate USD:BRL is R$5.75 reais for $1 USD. This meant that I just ate enough food for two people, with a drink, for about $8!

My initial thoughts—“There’s no way the food is this cheap in a neighborhood like this. Brazilians live in paradise!”

But what I didn’t realize was affordability depends on who you are, where you earn, and what pieces of paper you have in your pocket. While this meal is a bargain for me, for most locals earning Brazilian wages, eating like this might not be so much of an afterthought. My conclusion that Brazil is a paradise might hold truth, but the first part of my statement lacks some crucial context.

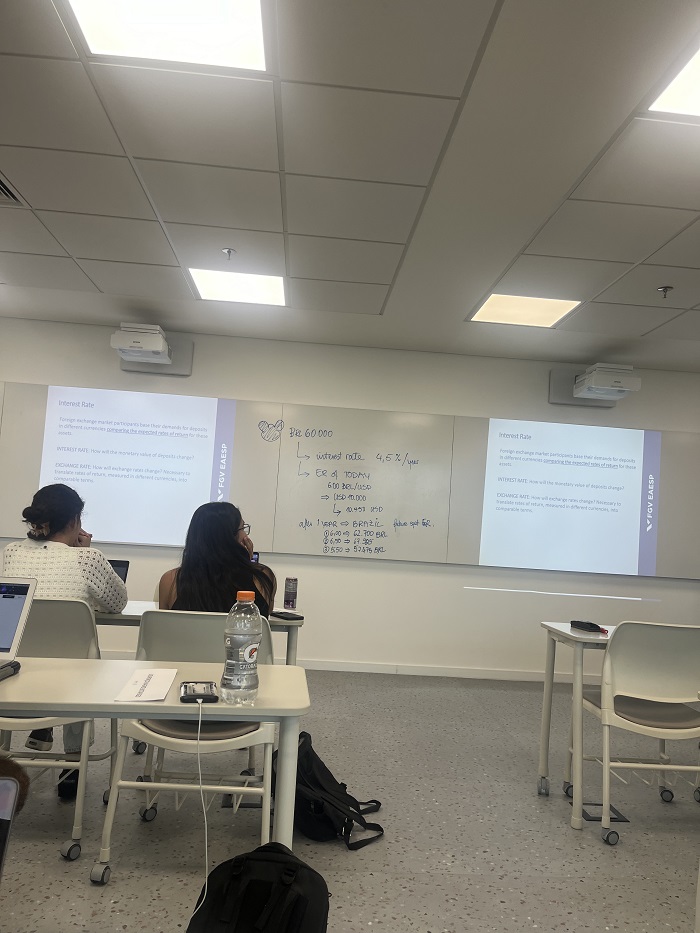

Left Image: I thoroughly enjoy my FGV International Finance class. I’ve gained so much knowledge on exchange rates, and I often feel challenged by my professor and the other students in the class. Luckily it’s all in English so I can keep up. One activity that our professor has us do is prepare a report of the current news headlines and discuss their impact on the subject material.

Right Image: One of the best places to exercise this price difference is at food markets! In D.C. where I got to college, I tend to avoid pricey street farmer’s markets and opt for produce from the supermarket. But here I wait for every Tuesday to come around for the weekly ‘Feira-Livre’ in Perdizes, where I can spend no more than R$100 for two arms full of fruits, eggs, vegetables and a pastel (traditional Brazilian snack).

In my International Monetary Finance class, we discuss exchange rates–how currencies appreciate or depreciate and how that impacts consumer behavior. Recently, we discussed the Big Mac index, a model that examines the price of a McDonald’s Big Mac in different countries to compare price level to exchange rate.

Having sampled many a Brazilian Big Mac, I know it costs approximately R$25, about $4.23 in USD. This is less expensive than the $5.69 I would pay back in the states. According to the Big Mac Index, this suggests that the Brazilian currency, the real, is undervalued relative to the US dollar, and the dollar has a stronger purchasing power here. As an American, I am benefitting from a high conversion rate as well as stronger purchasing power. This should be reason for total rejoice…but there are some caveats:

This mindset is dangerous for my own pockets. Just because things are cheaper doesn’t mean I should be spending more. I’ve learned so far that some of the same budgeting habits I use back at Howard–such as paying for one water bottle and refilling it, or opting for public transit over Uber–are just as effective in Brazil. Aside from taking advantage of cheaper travel and admission fees, I should remember that my bounty here isn’t endless.

I must also recognize my privilege as an American abroad and remain aware of the economic realities faced by many people in the same physical place as me. I made it clear to myself that I’m in Brazil to engage with an existing way of life, not to be on a 6-month vacation. This has forced me to rethink my spending habits and exercise some much needed financial discipline.

The beauty of the CET Socially Sustainable Business in Brazil study abroad program is how it blends financial education with socially conscious programming, encouraging me to think critically about my surroundings and myself.