Written by Dominic Bellido (Colby College), Student Correspondent for CET Beijing, Fall 2023

On a warm Wednesday afternoon, our teachers take us to the National Museum (国家博物馆), where our task is to understand more about the period of Reform and Opening Up (改革开放) in China. We take the subway, and when we come up from underground, I see Tiananmen Square rise into view from across the street, unwavering in autumn morning heat.

Once inside the museum, we join other visitors and crowd around a tour guide, who begins to take us through an exhibition detailing the early history of China. The first room is empty, except each of the four walls are covered by the sculptures and etching of a crowded country, rife with wandering spirits, clouds, and mountain stones jutting out from the plains. Our tour guide’s voice sails across each relief in a clear and pleasant tone that we follow from room to room.

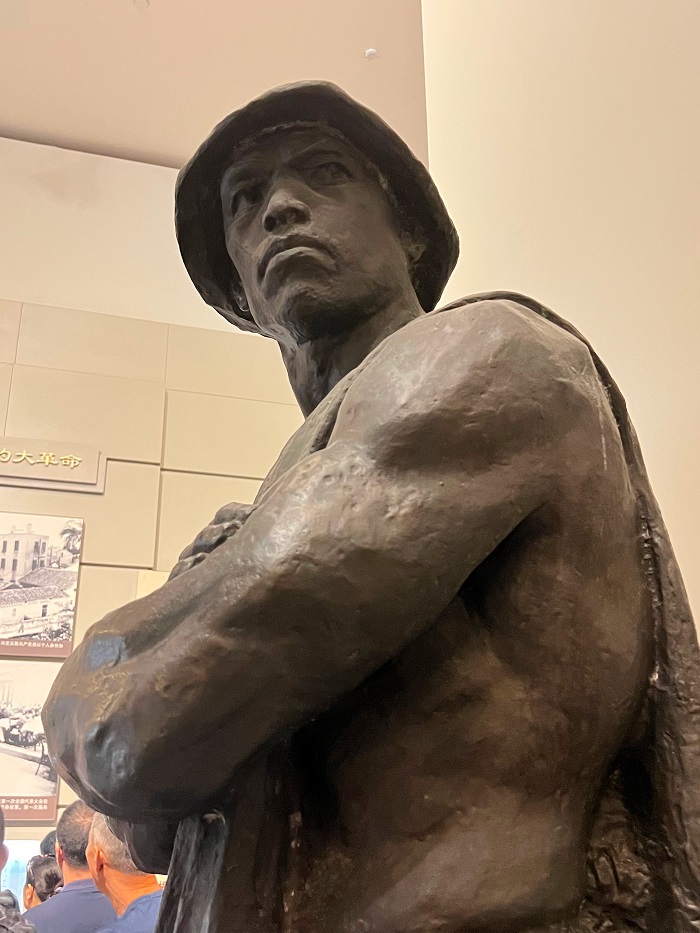

It is easy to distinguish this exhibition’s progress over time—the beginning contains multiple clay and stone sculptures, the faces of the early Chinese shaped by the artist’s hand to look rugged and realistic. I wander around the rooms with early dynastic paintings and portraits of ancient officials set beside 20th-century oil paintings depicting wars and celebrations. The styles of art span across decades, and yet, are all transfixed on depicting the story of life long ago.

Step by step, we make our way up to the second floor, moving along the corridors of Chinese history. We pass by copies of uniforms used by revolutionaries, yellow-edged poems, and notices of people like the Hong Kong seamen protesting for their pay. After a certain point, I elect to move ahead of our pack and wander around the exhibitions by myself. Ahead of the tour guide’s voice, I try to read the different slogans and advertisements, noticing the changes in style and form of 20th-century texts.

These changes align with the block texts of the exhibition summary posted at the beginning and end of each room; in their own words, the curators focus on the history from which modern China was born, describing the tumultuous struggle both against foreign imperial powers and the varying parties who all proclaim their philosophy as the one that will solve the poverty of rural China. When I arrive at the first room detailing the beginning of the Reform and Opening Up, I walk down the line of each glass cabinet and try to understand the writings and the numbers.

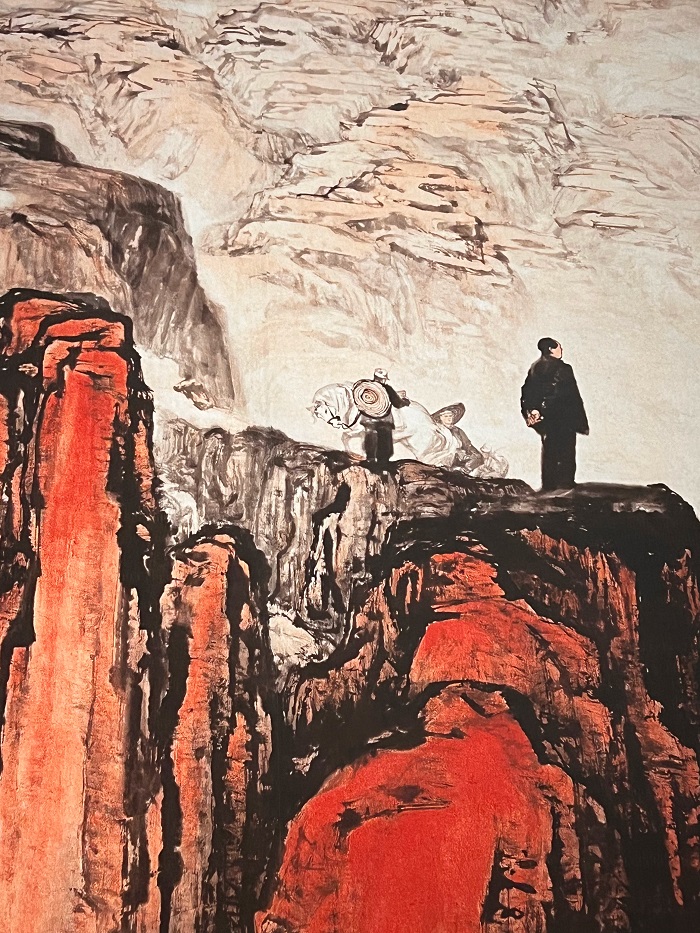

Painting of men atop a mountain, looking out into the great expanse of the world.

As helpful as the trip to the museum was, seeing each exhibition made me realize how difficult it is to capture the full extent and impact that this policy reform has, and still has, on the Chinese working class. To me, a museum is at its best when the art plays the role of an “opening act”—art can attract viewers, people who would have never normally paid attention to certain histories or stories, but the art could never explain every corner, every lasting effect of the content it portrays.

In this way, our trip to the National Museum did not leave me empty-handed; while our time was limited and the history too broad, I felt motivated to do my own research into certain sections of the history that I personally found interesting. It’s rare that a museum will do this for me. And at the end of the guided tour, when our guide said goodbye, we passed by one final room to exit, empty once again, save for the same-styled wall reliefs of the everyday working class. I say goodbye to the sculpted portraits of men and women dancing, working, lifting their faces towards the sky, and whatever new change it will bring tomorrow.