Written by Laura Romig (Brown University), Student Correspondent for CET Beijing, Summer 2023

At least I don’t have to give my presentation right after the girl who used physics equations. This was a comforting thought as I stepped to the podium at Renmin University. I was a flattened butterfly, pinned against the PowerPoint screen by the collective gaze of a room full of economics professors and students. In neat rows, behind placards printed with their names, my American classmates and Chinese peers gleamed in their best button-downs and dress pants, skirts, and ties. Five years from now, I could imagine each of them, young professionals working in China or America, speaking Chinese in business meetings. Somehow, that thought was comforting, too. I caught a smile from classmates and teachers, gripped the microphone, and began my presentation in Chinese: Agriculture is maybe humanity’s earliest form of technology. It represents the harmonious cooperation between humans and nature…

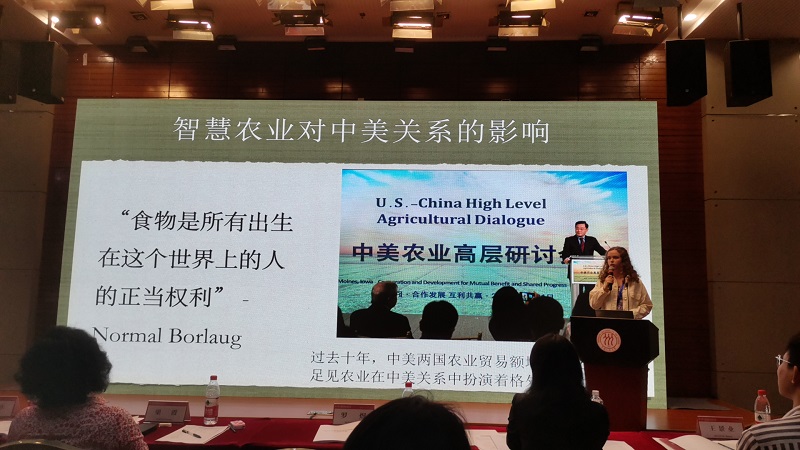

I spoke for eight minutes about the future of intelligent agriculture and its significance for US-China relations. Sometimes I momentarily forgot what I had planned to say; sometimes, I pronounced a word wrong or with the wrong tones, had to backtrack and say it again; my hands shook around the microphone. But as I walked back toward my own name placard, heartbeat still skittering, I felt that I had crossed some boundary, struck new ground, though I wasn’t yet sure where.

Here I am presenting about intelligent agriculture and US-China relations, but you can’t tell how nervous I was!

In a previous blog post, I compared learning a second language to arriving at the foot of a mountain and beginning to climb. As you scramble between rocks and vines, you can take advantage of certain footholds and ropes for assistance— a dictionary of vocabulary, or the grammar structures in your textbook, for example. But these footholds can only take you so high. As I lived in China for two months, speaking Chinese as a necessity, I slowly realized that many of the footholds remaining above me relied on more than just descriptive sentences about myself or the world. I needed words that meant action, words with the power to act— speech acts.

What’s a speech act? A greeting, a promise, a request, a word of thanks, for a few examples. In our first languages, we pick up speech act etiquette through observation and immersion— the first few years after birth being the ultimate language immersion program. But while learning a new language later in life, we have to discern the guardrails around speech acts through a combination of professors’ formal instruction and, if we’re lucky, trial and error in a language environment like the one cultivated at CET Beijing. And as we learn to apologize, accept a gift, complain, and properly greet a best friend or stranger, we learn how to exist as fully-rounded people in a second language, not just caricatures— we climb the mountain.

Giving a speech is not a speech act in the traditional definition, but public speaking is, in my mind, one enormous action, making a statement about yourself to a crowd, a challenge even in one’s first language. When our teachers had initially explained the opportunity to speak at the forum, I was at best unenthused, at worst petrified by the notion of talking for ten minutes in Chinese to strangers. But with their encouragement, I prepared a presentation. Speaking at Renmin University’s International Monetary Forum was an opportunity I could never have had in the US— not only to present on economic topics to Chinese professors and students but also to meet them and have conversations, and to listen to their (much more thoroughly researched, and illuminating) presentations and perspectives on global relations, the future of the economy, of technology. Giving my own speech opened up avenues to conversations, connections, and friendships with the other students, the young professionals whose future vision I had seen standing at the podium.

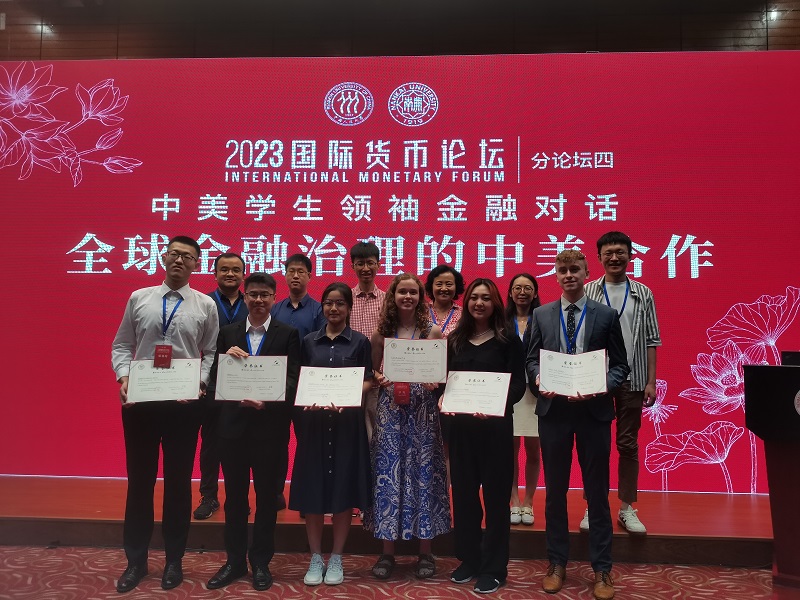

American and Chinese students with university professors at Renmin University’s International Monetary Forum

After I gave that presentation, I had my first foothold in Mandarin public speaking. The next week, our class visited a bookstore in preparation for our presentation the next day, in which we would recommend a literary work to the class. We perused the antique maps of the city, the Beijing history texts, and the children’s stories that seemed more suitable to our character recognition ability; I wandered through the shop’s stone courtyard, grass overgrown around a Buddhist tower yearning skyward in the center, a lone cat stretching in a patch of sun, serene. The next day, I gave what I think was my best presentation in Chinese I’ve made so far about Ursula Le Guin’s speculative fiction masterpiece, The Dispossessed. I didn’t write or memorize a script; my hands didn’t shake. Instead, I just spoke and molded my sentences to the ideas I already had, catching onto vocabulary words or grammar structures that floated to the top of my mind.

Studying a language abroad, especially in a well-planned program like CET, often offers up opportunities such as the forum we joined, opportunities that seem daunting, seem like extra work, opportunities far beyond the close suburbs of your comfort zone. My advice is simple: if you see one of those opportunities, you are lucky. Take it.

My CET class, Chinese 400, with our graduation certificates after completing the program

In the final week of the program, another such opportunity appeared to represent our class by speaking at our graduation ceremony, and I volunteered. But as I sat at my dorm desk to write the speech, hands hovering over the keyboard and lamplight flickering over one of my last nights in China, I could feel that this wasn’t just some chance to develop my public speaking. Somehow, in the characters I typed out, in the few remaining moments I had in Beijing, in the actions I took over the next few days, I had to say goodbye.

A goodbye is a speech act, too; tried-and-true, we practice it daily, parting ways after spending time together, seeing family off to work or on a trip. The everyday, mundane goodbyes in Chinese I understood— 再见 for goodbye, or its cutesy counterpart 拜拜, which sounds like “bye-bye,” maybe even 明天见, 会儿见, “see you tomorrow,” “see you in a bit .” But “see you in a bit” was actually a trick, a ploy to avoid having to truly say goodbye, a reassurance that there was no need for farewell if you would see the person again so soon. This speech I was writing was no everyday goodbye. It was goodbye to a city, to a country, to a culture, a language; goodbye to a program, to friends from across the US or the globe all scattering off to their own paths. It was “goodbye, all of us will likely never again be in the same space together.” “Goodbye, I don’t know when I’ll see you again. I don’t know if I’ll see you again.”

How to say goodbye like that in Chinese? The truth was, I could hardly say it in English. Against the blank page, on which I had written a meager 大家好 (hello everyone), the cursor blinked up at me.

Leaving Chengdu after our program trip, we’d had a trial run at goodbye, saying farewell to our language partners and friends after four days together. In the muggy dark that July night, my language partner had taken us to a convenience store to buy breakfast for the train, exchanged emails with me, and crowded us together for photos. I had done my best to express my gratitude for her and our time together. That was a template to learn from, I thought— showing care for the friends in their departure, establishing ways to stay in contact, commemorating with photos, verbalizing gratitude. CET had given us an impossible task— to say goodbye to these experiences and friends— but it had also, in its programming, given us this opportunity to learn how.

My CET classmates and I performed martial arts at the Chinese cultural night after the forum

After I finished typing a draft, I read through it. The word I had used the most was simply 朋友 (friends). Friends, meaning my American classmates and roommate, my Chinese language partner, my martial arts class instructor, the other students at the university, our teachers. Accordingly, I texted two of my Chinese friends then, asking if they could help me edit the speech. When I met up with them the next evening, under the familiar fluorescent glow of the campus coffee shop, they helped me elevate the speech and address everyone with respect and proper grammar. After an hour or so, I thought we had finished, but my friend Jade gestured to the ending and said: “I think you should add a poem.” She paused. “I know the perfect one.”

The poem my friend typed out at the end of my speech was this: 海内存知己,天涯若比邻. It means, roughly, that even if dear friends are separated by the sea and the forces of the world, their hearts are still just as close as neighbors are in distance. Saying it aloud at our graduation ceremony felt like an action. I was speaking that future into existence, our hearts as close as neighbors. I could describe in detail that moment when I gave the speech, but it seems to me that the speech wasn’t truly the goodbye— it was the three of us crowded around my computer screen until the closing bell, to the baristas’ chagrin; it was the notes and gifts exchanged between classmates and language partners on the final day; the CET students all squeezed around the tiny patio table on the last night, English interspersed with Chinese after the Language Pledge ended; it was a group of my friends planning a goodbye dinner for Monday evening, and in the end having dinner every night after that until we left.

While studying abroad for a language, that language becomes more than just the vocabulary and grammar structures trapped within the walls of a university classroom. The language transforms into action, into a long list of actions you take every day just to get from one place or situation to the next. Whether that action is learning to have the confidence to speak in public, to order food, or to say goodbye to dear friends, grasping each new speech act is a step further in the language, a step difficult to take while studying in the US. Abroad, the footholds you climb to learn the language become inseparable from the experiences and relationships in your own life.

In Chinese, the most common word for goodbye, the word every first-semester Chinese could tell you, is 再见. 再 meaning “again,” and 见 meaning “see”: “See you again,” in literal translation. Earlier, I said this was cheating at goodbye, pushing it off until the next time. But now it seems to me like a declaration— telling the person, despite the circumstances we might be in, despite the uncertainty of the world, I will see you again. Saying goodbye just means speaking that future into existence. From my first semester of studying Chinese to my graduation ceremony at CET, I practiced this speech act. Saying goodbye, but meaning “We will see each other again.”