Written by Laura Romig (Brown University), Student Correspondent for CET Beijing, Summer 2023

I had just arrived in China, sticky with sweat and anticipation. And I was on my way to a Domino’s?

After thirty total hours of travel, eight of them spent wandering the Doha airport and an hour-long bus into the city, I had scrambled across the patio and between the sliding doors of a brick structure streaked with ivy and nestled between sky-scraping trees in dark summer green. As if there were any doubt where my travel had taken me, bright stacked Chinese characters on the facade announced the building’s name: 中国房子 or, in English, China House.

Waiting on the patio, my language partner 唐慧, or Tang Hui, a first-year graduate student at Capital Normal University, introduced herself and then explained that the student dining hall was already closed, but we would walk to a nearby restaurant for a quick dinner. I followed her and a group of other students as she confidently navigated between the zippy delivery scooters and primary-colored bicycles for rent cluttering the sidewalk and crosswalks.

Almost familiarly, the city street thrummed with anxious turn signals, packs of uniformed high school students, and a June humidity that sank beneath my skin. Despite the heat, many women carried umbrellas or wore light jackets and face masks—not for rain or sickness, but to prevent themselves from tanning in the sun, Tang Hui explained. Ducking around them, we passed bright storefronts labeled with Chinese characters until stopping beneath one in red, white, and blue, painfully familiar.

At Domino’s, or 达美乐比砸 in Mandarin, Tang Hui ordered the meal by scanning a QR code with her phone and selecting our choices; we ate, at a sit-down table unthinkable in the US version, pizza topped with duck meat and a sweet sauce characteristic of Beijing’s famous dish, Peking Duck. Later, I asked Tang Hui if she had taken us to the pizza joint because we were from the fast-food-obsessed US, and she said no—it’s just a popular place for dinner.

A visit to the Beijing Summer Palace (颐和园) with classmates.

That initial meal was the beginning of many firsts in Beijing, but it also encapsulates well what it’s like to live in a globalized, major city that is supported by a robust web of technology, experiencing authentic aspects of Chinese culture and history interwoven with modern and Western influence.

In Beijing, for example, your phone is an all-powerful object. Almost everything, it seems, is accomplished by scanning a QR code. Ride the subway? Order food in a restaurant? Buy tickets for a tourist site? Enter the university? Check out at a store? All done through your phone, straight through WeChat or Alipay, practically super-powered apps that I quickly downloaded. My first time on the Beijing subway, I fumbled through the app and then scanned the code on my phone, under the watchful eye of Tang Hui, and it worked perfectly.

The subway—brisk and cool, quiet, packed with commuters and students tapping away on their cellphones—rushed me away to the Olympic Athletic Center, where I practiced ultimate frisbee with a local women’s team. On the field, Mandarin and English intermixed freely, conversation crossing the spaces between languages quick as the snap of a handler’s wrist before a downfield throw. Sometimes to cut on the field was “cut”; sometimes it was 跑. Under silvery night lighting, with the Bird’s Nest Stadium from the 2008 Olympics looming just beyond the highway, the frisbee field became a practice arena for language, its limits and its extensions between people and cultures.

Thanks to Tang Hui, I’ve become adept at navigating WeChat’s seemingly endless features, including booking tickets to Beijing’s sprawling tourist sites, just in time for the waves of summer domestic tourism sweeping through the city. At my first tourist destination, 天坛公园 or the Temple of Heaven, I wandered across open, wide squares, flanked by intricately painted and sculpted halls for prayer, climbed stairs that were always in multiples of the sacred, long-lasting number 9, and peered into the cool, dusty spaces where ancient Chinese emperors would worship the gods and wish for good fortune. Backpacked, camera-attached tourists interspersed with joggers and locals playing 毽子, also known as Chinese hacky-sack; in one secluded garden, my friend and I found a group of women dancing 广场舞 or the square dance, and slid into the back row to join, following the leader’s movements to the music. We wandered among the ancient, divine history with our QR code tickets in our pockets, portable fans between our hands whirring away the heat.

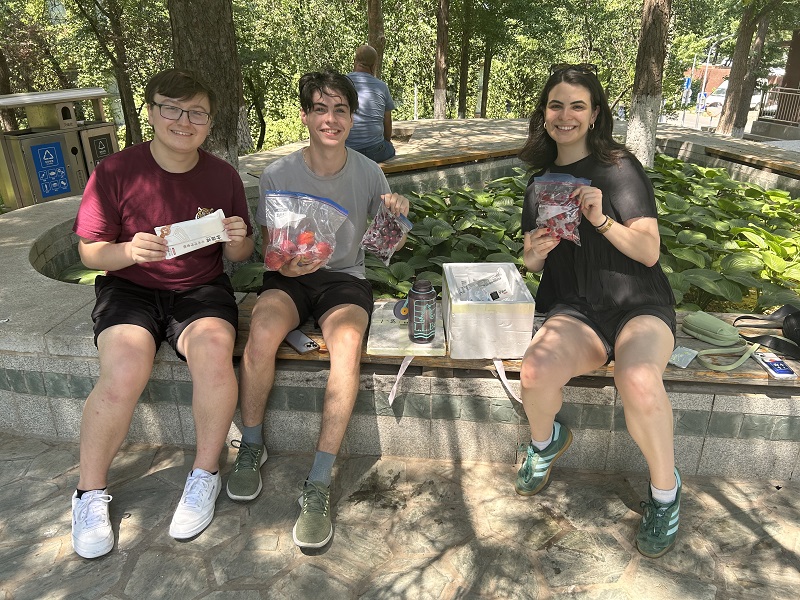

My classmates and I eating freshly delivered fruit at the campus park.

Luckily, gadgets aren’t the only way to beat the Beijing summer temperatures. Later, I sat with three students from the program in a small park on our campus, crowded around a small cooler box. It had been presented to us, almost miraculously, by one of the men on delivery bikes that speed around the city as dictated by delivery apps, heavy Beijing accents in tow. Inside the box were fruits and ice cream, pleasingly cold and round to hold, peaches and cherries and popsicles that we passed between us.

There have been other firsts: the first steaming copper hot pot, cooked meat fragrant with a Beijing specialty peanut sauce; the first martial arts lesson, where my quads burnt with the effort and my mind spun to make the Chinese instruction fit with the physical experience of my body, which I know best in English; our first row of tourist trap-like shops, lining the streets beyond the Drum Tower originally built in 1272; our first debate in Chinese class, where the six students in my class primly argued the benefits and disadvantages of high technology; the first chrome-shiny shopping mall; the first national holiday, 端午节, when we ate zongzi, a sticky rice balls with filling wrapped in bamboo leaves.

Classroom debate about the benefits and disadvantages of technology.

In my class, which I attend from 8am to 12pm every weekday, we read an essay discussing the difficulty for cities with long histories to both preserve that history and ancient culture, as well as enter the modern era and accrue economic success. The writer compared striking this balance to creating a “double-sided embroidery,” where instead of a knotted back-side hiding any mistaken stitches, the reverse face of an embroidered fabric shows a second image, just as vibrant as the first—an intricate, technically difficult feat. On one side, the glistening image of technology, wealth, and globalization; on the other, winding rivers and high gates, narrow hutongs and ancient art, the impressions left on a city by history’s footsteps.

As I’ve experienced living in Beijing over the past two weeks, I’ve been stepping through this precisely woven fabric, this delicate two-faced embroidery that, in the physical world, feels almost infinitely-sided: tradition and history, cellphones, convenience, English and Mandarin, tumbling children and adults rushing after them, wheels scraping over newly paved streets, a Buddhist temple rising skyward between banks and coffee shops. All of it was one beautiful fabric that, thanks to my language study, I’ll be woven into for the rest of the heat-drenched summer. As I walk across our campus, perch myself on subway seats, and watch a single lotus flower bloom at the Summer Palace, I find comfort in letting myself be part of the embroidery.

A classmate, my language partner and I at a Buddhist temple in the middle of Beijing’s finance district.